Presentation:

Sarah, a 35 year old Flight Attendant called the clinic asking for an appointment. She’d been referred to us by Dr Tim Wade-Ferrell from Carlingford NSW.

Symptoms:

Sarah’s chief complaint was sudden onset lumbo-sacral pain. The pain was described as a “strong, dull ache, with occasional sharp stabs”. She was markedly antalgic to the right, there were no symptoms of Cauda Equina syndrome or sciatica but she had a strongly positive Valsalva sign.

History:

Sarah was a very competitive sportsperson. She’d played Basketball at very high level since she was 7 years old, as well as Netball. Her immediate family were similarly sporting, all of whom competed at a very high level. Several members of her extended family were professional AFL players. Sport was central to her life.

She had previously suffered a left tibial plateau fracture from basketball in July 2001. There was no history of surgery. She had contracted Herpes Zoster when she Xyrs old and CFS from X to X. There was some suspicion that this had left her with the IBS and Fructose Intolerance that she was still experiencing.

Her current symptoms began very suddenly. She’d been recently married and the stress of the preparations left her quite run down. Her depleted immunity gave onset to laryngitis and bronchitis, which led to extended bouts of heavy coughing. It was during one of these episodes two days after her wedding that she bent over the sink to cough and felt a sudden, sharp jolt of pain at her lumbo-sacral junction.

She saw an Osteopath for several weeks, which gave temporary relief but no resolution. At a loss for a better solution, the Osteopath cleared her to return to work.

Sarah had mentioned her predicament to her aunt who worked as a CA for Dr Tim Wade-Ferrell in Carlingford NSW. Her aunt asked Tim what her niece should do and he suggested she see us.

Examination:

Sarah was a tall (183cm) young woman, with a slightly built yet athletic physique. She struggled to rise from a seated position when called into the Examination room. There was a clearly visible antalgic posture, forward and to the right.

Orthopaedic:

Cervical ranges of motion were all slightly reduced without pain, especially in lateral flexion. This was suggestive of DJD or Facet Arthrosis in the mid to lower cervical region. Cervical flexion in the standing position produced a slight increase in the lumbo-sacral pain, suggestive of dural traction.

Lumbar ranges of motion were all restricted by muscle contraction. Extension and left lateral flexion which were not possible past vertical without lancinating pain localised to the lumbo-sacral region, particularly on the left.

Supported Adams Test confirmed that the source of the pain was most likely of lumbo-sacral rather than SIJ origin. Oblique range of motion testing indicated that the origin was either the left lumbo-sacral facet complex or an L4-L5-S1 disc lesion.

A slump test was not performed due to the pain she experienced while sitting.

Neurological Examination:

All cranial nerves tests were normal and bilaterally equal, as were deep tendon reflexes in both upper limbs.

Deep tendon reflexes in the lower limbs were normal bilaterally with exception of the left Achilles, which was markedly reduced.

Sarah reported no numbness or paraesthesia, however she was unable to heel walk easily on the left. Further examination of this revealed a slight foot-drop.

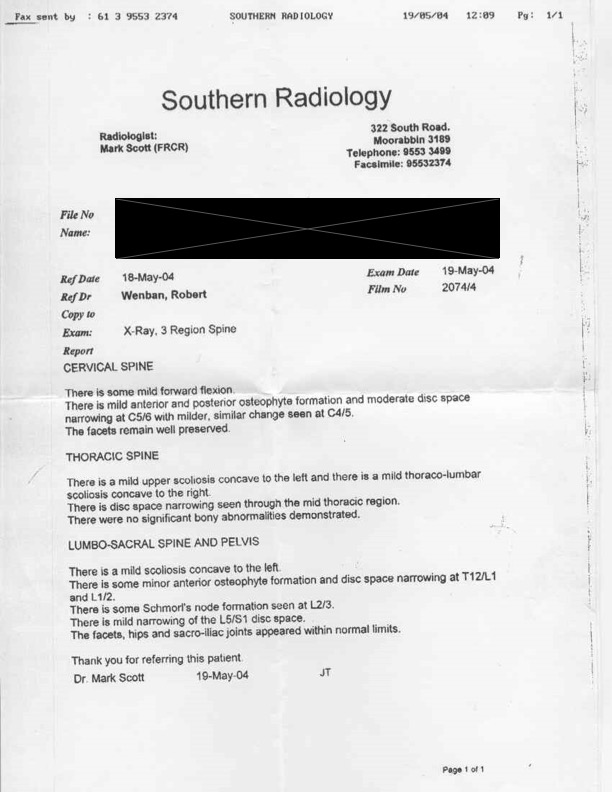

Imaging:

On the basis of the above test results, it was determined that Sarah should have X-rays to rule out pathology or anomaly before any treatment be given. She was given a referral for weight baring plain films and advised to rest and apply ice until the images were assessed. I also told her to make another appointment so I could go through the images with her.

I suggested that she bring someone else with her during the Report because there would be a lot of information to take in. Experience had shown that there is a much higher retention of information when patients are able to discuss the Report of Findings with another person when they get home.

(See report below)

Diagnosis:

There were clinically significant appearances on the films that were unreported by the Radiologist. Sarah had asymmetry of the orientation of the lumbosacral facets (facet tropism) and asymmetric SIJs. She also had complete reversal of the cervical lordosis secondary to extensive DJD from C4-T1, as well slight spurring on the superolateral aspects of both acetabula.

These are often unreported by Radiologists because they view them simply as variants of normal, however they can make a significant difference to how we manage a patient’s issues.

The mildly narrowed L5-S1 disc space supported the suspicion of facet imbrication; however by extension, it also pointed to a past history of disc injury. In light of the symptoms:

- The nature of the pain

- Positive Valsalva sign

- Antalgic posture

- Foot drop

- Reduced left Achilles reflex

It was decided to manage this as a primary disc injury.

Report of Findings:

When Sarah presented for the Report of Findings the following day we went through the films and test results together.

She was quite shocked at the relatively worn state of her spine given her young age. I asked if anyone else in the family had similar issues and she said that both parents had spinal pain and arthritic changes.

Both she and her mother asked if it “could be fixed and if so, how long would it take?” I told them that it could almost certainly be improved but would take time. I said that I didn’t know how long it would take, firstly because everyone has a different rate of healing, and second, I had no control over what she did once she got off the table. Having said that I reassured them that the worst of the symptoms should be reduced significantly within a couple of weeks, but that didn’t mean it was “healed” – that could take several months.

Treatment Given:

Considering the still very tender nature of Sarah’s lower back she was initially treated using SOT. Her most frequent listing was Category 3, Right short, Neutralise T4 (CMRT), and cervical release using Cervical Stair Step.

Her initial response was very good but as is so often the case, after the primary muscle spasm eased, the true nature of the problem exposed itself. I then had to change to AMCT. The most common listings were Left AS, Left L3, Left T12, Left C5, all with an Activator 3 set at Setting 3 for the pelvis and lumbars, Setting 2 for the thoracics and Setting1 for the cervicals.

Progress & Outcome:

I was seeing Sarah twice per week. The antalgia and positive Valsalva sign were both gone after the second adjustment, and by the end of the second week she was much more comfortable. After three weeks she was able to walk easily, the foot drop had resolved and the Achilles reflex had returned to full function.

The nature of her work involved lifting heavy bags into overhead lockers and a lot of bending. Most important though was that the role of a Flight Attendant is primarily that of Safety and Crisis Management. For this reason I did not clear her to return to work until I was certain that she could act quickly and fully in her role should a major incident occur. This took a total of six weeks.

She was also then clear to return to her beloved basketball.

Discussion:

Probable Causative Factors-

Sarah’s case was a clear demonstration of two key predictors:

- Genetic predisposition

- Micro trauma during the growth period

Sarah’s family tree had generations of osteoarthritis scattered throughout the maternal and paternal side. So it was not surprising that a young woman should have the degree of DJD in the cervical region that we would usually expect in a patient twice her age.

The regular micro-trauma associated with the repeated small impacts of basketball are most likely to have occurred simply from the rapid acceleration/deceleration, stop-start actions of running on a high grip surface. This effect appears to be less pronounced in cases where the person began their “high impact” sport after the growth period.

Choice of Diagnostic Procedures-

Factors considered when choosing the type of adjustment procedure included:

- Degree of pain during the acute phase

- Sarah’s ability to move, relax or assume positions required for the various adjustment procedure choices

- Likelihood of aggravating an already compromised disc

Diagnosis Rationale-

The possibility of an SIJ injury was ruled out by the Supported Adams test.

Several of the test results brought the possibility of a facet issue into the differential diagnosis. These were dismissed by much clearer indicators for a disc injury. The positive Valsalva sign, indications of dural traction with cervical flexion, focal nerve root involvement signals, including reduced Achilles reflex and incipient foot drop all combined to point towards a disc injury.

Delivery of the Report of Findings-

Correct delivery of the Report of Findings is crucial to the patient. They’re usually frightened and frustrated and are looking to you for good news. Tip-toeing around the issue doesn’t help instill confidence, yet a brutal delivery can be perceived as “heartless”.

It’s important to explain the situation calmly, clearly, with care, and in terms the patient can understand. Jargon should be avoided at all costs.

Expectation Management-

Patients in Sarah’s position are often experiencing pain at a level they’ve never encountered before. They’ve probably been told everything ranging from “this is nothing, don’t be a baby” right up to “life as you knew it is effectively over”. The truth is always somewhere in the middle.

Be honest. If you think it’s going to be weeks rather than days to respond, say so. Don’t say it’s going to be months when you know it’s more likely to be weeks. If you don’t know, say so. Be honest.

Treatment Regime Choice-

If you only know one system of adjustment, this is easy. Do whatever you’re best at. If for instance, the patient has had Gonstead previously but you’re not as good at that as you are with SOT, use what you’re best at.

If you have many strings to your bow, be sure to use that which you think will bring the best results in the quickest time and in the safest manner.

If you’re only good at high force manual techniques but the patient could be put at risk by using them, be realistic with yourself and honest with your patient. Refer them on to a colleague who’s good at what the patient needs. Just because a patient came to Your clinic doesn’t mean they’re Your patient.

Progress Monitors-

You will have better patient compliance and therefore better long term outcomes if you have a way of measuring their progress other than self reported symptoms.

As we all know, the presence or absence of pain is one of the least reliable indicators. There are far too many factors that influence a patient’s pain perception to list here. However, remember that as unreliable as it is, pain is often the only indicator a patients has, so don’t dismiss it, but don’t use that alone. Whatever system you use, make sure you have a reliable way of measuring the outcome and then be able to demonstrate that to the patient.

Explain to them that you can’t tell what they feel, and they can’t tell what you measure, but between both of you you’ll have most of the information. So they tell you how they feel, you tell them what you measured.

Doing this will shift the patient’s focus from pain management to health management.

Transition from State of Injury Restriction to Normal Function-

This is where reassurance is vital. The patient needs to know that they are getting better, and will continue to get better as time passes. There may still be lingering fears of regression but these can be allayed by clear and honest communication.

Transition from Acute Care to Maintenance-

As the patient progresses, their focus will move away from pain. If you’ve been able to demonstrate their progress beyond the pain threshold, they will be more willing to follow your advice. This then produces better ongoing results for the patient and a smooth transition from symptom based crisis care to health optimising Maintenance Care.

“If it’s never been right, you don’t know it’s not right until it hurts.

Once it’s been right you’ll know as soon as it’s not right.”